TNF Inhibitor TB Risk Assessment Tool

Risk Assessment

Recommended Screening Approach

Treatment Recommendation

Critical Monitoring Guidance

Why TNF Inhibitors Can Trigger Tuberculosis

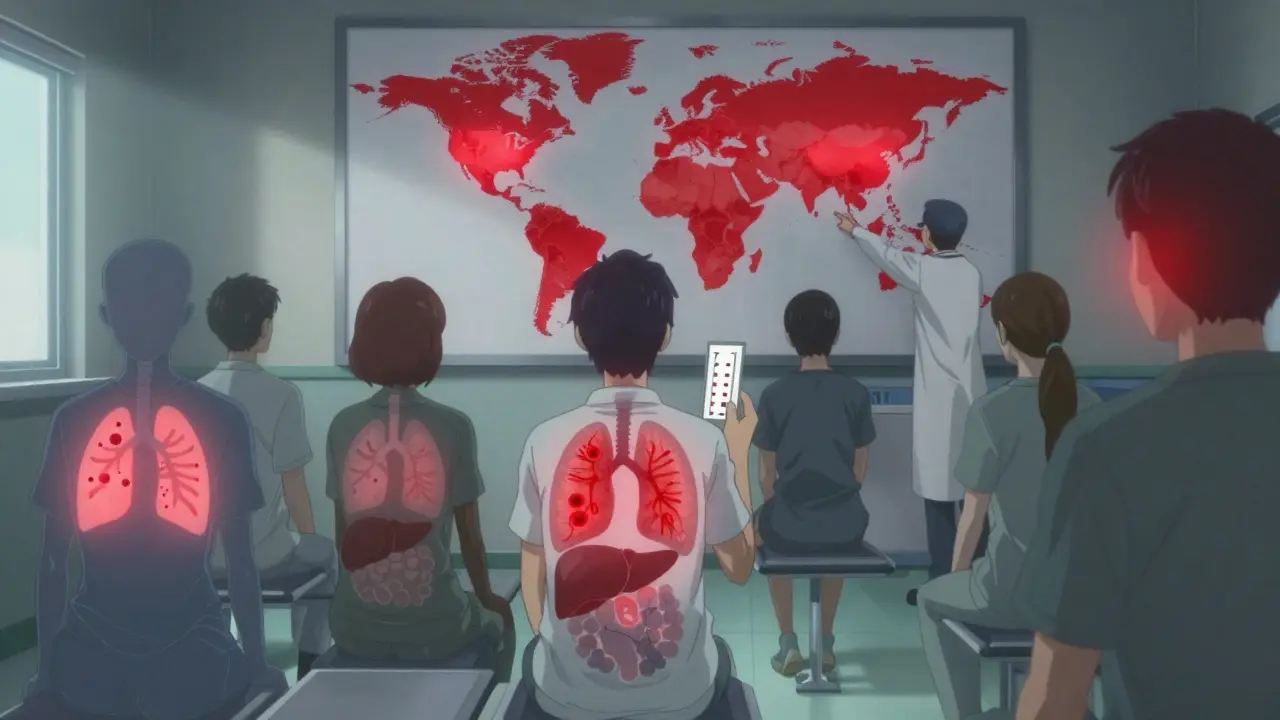

When you take a TNF inhibitor like adalimumab or infliximab, you’re not just calming down your immune system-you’re disabling one of its most important defenses against tuberculosis. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) isn’t just another protein. It’s the glue that holds TB granulomas together. These are the tiny, wall-like structures your body builds to trap the TB bacteria and keep them from spreading. When TNF-α gets blocked, those walls crumble. The bacteria wake up. And suddenly, a quiet, harmless infection becomes a life-threatening disease.

This isn’t theoretical. Studies show patients on infliximab or adalimumab are more than three times as likely to develop active TB compared to those on older drugs like methotrexate. Even among TNF inhibitors themselves, the risk isn’t the same. Etanercept, which works differently, carries a much lower risk. Why? Because it doesn’t bind as strongly to the version of TNF that sticks to cell surfaces. That’s the version your body needs to keep TB locked down. Antibodies like infliximab and adalimumab tear it right off.

Who’s at Risk-and How to Find Out Before Starting Treatment

Screening for latent TB before starting any TNF inhibitor isn’t optional. It’s mandatory. The American Thoracic Society, CDC, and Infectious Diseases Society of America all agree: test everyone. No exceptions. The two standard tests are the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). Neither is perfect. TST can give false positives if you’ve had the BCG vaccine. IGRA is more specific but costs more and isn’t available everywhere.

Here’s what real clinics are seeing: in a 2019-2024 study of 519 patients, 87% got a TST, 37% got a booster TST, and only 6% got IGRA. That’s not enough. Many patients with negative tests still developed TB. Why? Because screening can miss recent infections. It can miss people with weak immune systems. It can miss TB that’s hiding outside the lungs. That’s why guidelines now say: if you’re from a country with high TB rates-more than 40 cases per 100,000 people-treat you for latent TB even if your test is negative.

What to Do If You Test Positive for Latent TB

If your screening comes back positive, you don’t start the TNF inhibitor right away. You wait. You treat the latent infection first. The gold standard has been nine months of isoniazid. But that’s hard to stick with. Side effects like liver damage make 32% of patients quit. That’s why new options exist now. A four-month combo of rifampin and isoniazid was approved by the FDA in 2024. It works just as well, with far fewer people dropping out. In trials, adherence jumped from 68% to 89%.

Some doctors still prefer three months of rifampin alone or a single weekly dose of rifapentine and isoniazid for 12 weeks. All of these are better than skipping treatment. And yes, even if you complete the full course, you’re not 100% protected. But your risk drops by 80-90%. That’s the difference between a rare event and a preventable tragedy.

The Hidden Danger: TB That Shows Up After Treatment Starts

Here’s the scary part: 18% of TB cases in TNF inhibitor patients happened even when screening was negative. In one case, a patient had two negative TSTs before starting adalimumab. Three months later, they were hospitalized with TB in their spine and liver. No cough. No fever at first. Just weight loss. That’s the problem with TB on biologics-it doesn’t act like regular TB. It’s often extrapulmonary. It spreads to bones, joints, lymph nodes, even the brain. And it’s harder to diagnose because symptoms are vague.

Doctors are now told to check for TB every three months during the first year of treatment. Look for night sweats, unexplained weight loss, fatigue, low-grade fever. If you’ve been in close contact with someone who has TB, or if you’ve traveled to a high-risk country since starting treatment, tell your doctor immediately. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse.

Why Some TNF Inhibitors Are Riskier Than Others

Not all TNF inhibitors are created equal. The data is clear:

- Infliximab and adalimumab carry the highest risk. Both are monoclonal antibodies that bind tightly to both forms of TNF, including the membrane-bound version critical for granuloma stability.

- Etanercept is a soluble receptor that binds mostly to free-floating TNF. It leaves the membrane-bound version mostly intact. That’s why its TB risk is roughly one-fifth of the others.

In the British Society for Rheumatology study, patients on infliximab had a 3.3 times higher TB rate than those on etanercept. Adalimumab was nearly as risky. That’s why some rheumatologists now choose etanercept for patients from high-TB-burden regions-even if it’s slightly less effective for their arthritis. Risk reduction matters.

What Happens When TB Strikes During Treatment

When TB reactivates on a TNF inhibitor, it’s not just a simple infection. It’s often aggressive. About 78% of cases involve organs outside the lungs-joints, spine, liver, brain. Standard TB drugs like isoniazid and rifampin still work, but stopping the TNF inhibitor is critical. In some cases, doctors have to pause the biologic for weeks or months.

And then there’s TB-IRIS: immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. This happens when the immune system, after being suppressed for months, suddenly wakes up and overreacts to the dying TB bacteria. It causes fever, swelling, pain-even in places where the infection was already treated. In one study, 12.7% of patients on anti-TB therapy developed IRIS after their last TNF infusion. Treatment? High-dose steroids, sometimes for months. It’s a dangerous balancing act: kill the TB without triggering an immune meltdown.

What’s Next? Safer Drugs on the Horizon

Researchers are working on next-generation TNF blockers that don’t wreck granulomas. Early animal studies show a new class of drugs-targeting CD271 instead of TNF directly-can reduce TB reactivation by 80% compared to traditional inhibitors. These are still in Phase II trials, but the results are promising. If they work in humans, they could change everything.

For now, the message is simple: know your risk. Get screened. Treat latent TB. Monitor closely. Don’t assume a negative test means you’re safe. And if you’re on infliximab or adalimumab, especially if you’ve lived in or traveled to a country with high TB rates, stay alert. Your immune system is working harder than you think to keep you alive.

Real-World Challenges: When Screening Fails

It’s not just about tests and guidelines. Real life gets messy. In clinics with limited resources, IGRA isn’t available. Some patients skip follow-up visits. Others refuse isoniazid because they’re scared of liver damage. One nurse on Reddit shared how she had to manage a patient from India who had a negative TST but was later diagnosed with TB after just two months on adalimumab. The test had failed. The patient had no symptoms until it was too late.

Another issue: 27% of patients face delays in starting treatment because their LTBI treatment paperwork got lost or wasn’t properly documented. That’s not just bureaucracy-it’s a health risk. If you’re waiting for treatment to begin, your arthritis is still flaring. But rushing into a TNF inhibitor without clearing latent TB? That’s a gamble no one should take.

Bottom Line: Don’t Skip the Steps

TNF inhibitors save lives. They let people with severe arthritis, Crohn’s, or psoriasis live normally again. But they come with a hidden cost. TB reactivation is rare-but when it happens, it’s often deadly. The difference between life and death often comes down to one thing: whether someone took the time to screen, treat, and monitor.

Screen before you start. Treat if needed. Watch for symptoms. Know which drug you’re on-and why it matters. And if you’re unsure, ask your doctor: "Have you checked for latent TB? Have I been treated for it? What’s my risk based on where I’m from?" Those questions could save your life.

12 Comments

Cam Jane

6 January, 2026Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest explanations I’ve ever read on TB reactivation with biologics. Seriously, if your doctor hasn’t walked you through granulomas like this, ask for a referral. I’ve seen too many patients get blindsided by this. Screening isn’t bureaucracy-it’s armor. And if you’re from India, Brazil, or Nigeria? Don’t wait for symptoms. Treat first, ask questions later. 🛡️

Matt Beck

6 January, 2026So… TNF is like the bouncer at the TB club? Block it, and the bacteria just walk right in?? 😳 I mean… wow. I’m on adalimumab and now I’m sweating bullets. Why didn’t my rheumatologist mention this like… I dunno… BEFORE I signed the consent form?? 🤯

Amy Le

8 January, 2026US citizens need to stop acting like TB is a ‘third-world problem.’ I’ve seen cases in rural Ohio. Your ‘negative test’ is a lie if you’ve ever been near a crowded bus station or a refugee center. The CDC guidelines are there for a reason. If you’re too lazy to get IGRA, you’re gambling with your liver, your spine, and your kids’ future. 🇺🇸

Pavan Vora

10 January, 2026From India here… I had TB as a kid, treated it, then got adalimumab for psoriasis. My doc said ‘no need to retest’ because I’m ‘from high-risk area’… but I got a negative TST. Three months later, I had spinal TB. They had to drill into my vertebrae. Please… if you’re from South Asia, Africa, or SE Asia… assume you’re positive. Treat it. Even if the test says no. 🙏

Stuart Shield

10 January, 2026God, this post reads like a thriller novel written by a brilliant immunologist. The granuloma-as-wall metaphor? Chef’s kiss. And the part about TB-IRIS? That’s the kind of thing that keeps me up at night. Imagine your immune system waking up like a bear from hibernation… and immediately punching your lungs in the face. Brutal. But necessary. 🧠

Susan Arlene

12 January, 2026so like… if you’re on infliximab and you’re from mexico or the philippines… just get the 4-month rifampin thing? even if your test is negative? that’s wild. i’m gonna ask my doc tomorrow. thanks for the heads up. 🤷♀️

Mukesh Pareek

12 January, 2026Let me be blunt: non-compliance with LTBI protocols is a public health failure. The 32% dropout rate on isoniazid? That’s not patient negligence-it’s systemic incompetence. Providers need to offer DOT (directly observed therapy), not just hand out prescriptions. And etanercept? It’s not ‘less effective’-it’s the only rational choice for high-risk populations. Stop the therapeutic nihilism.

Katelyn Slack

14 January, 2026thank you for writing this. i’m on adalimumab and i’m terrified. my test was negative but i’m from egypt. i didn’t know about the 4-month option. i’m going to ask my doctor about it tomorrow. you saved me from a nightmare. 🙏

Harshit Kansal

15 January, 2026my cousin got TB on infliximab. they thought it was pneumonia. turned out his spine was full of bacteria. he lost 40 pounds in 2 weeks. no cough. no fever. just… tired. like, soul-tired. now he’s on steroids and TB drugs and can’t walk. don’t wait. test. treat. listen.

Brian Anaz

16 January, 2026Why are we letting people from high-TB countries get biologics at all? This isn’t ‘personal freedom.’ It’s a public health time bomb. If you’re from India, get your arthritis treated with methotrexate. End of story. We’re not here to risk American healthcare systems for your lifestyle.

Vinayak Naik

16 January, 2026Bro… the 4-month combo is a GAME CHANGER. I was on isoniazid for 9 months, got liver issues, quit. Then my doc switched me to rifampin + isoniazid. I did it. No side effects. I’m now on etanercept. Life’s good. Don’t let fear stop you-just pick the right script. 🙌

Kiran Plaha

17 January, 2026so if i’m from bangladesh and got a negative tst… should i still get treated? or is that overkill? i’m scared to ask my doctor because i don’t want to sound dumb. any advice?