When you take a medication like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin, even a tiny change in dose can cause serious harm-too little and the drug doesn’t work; too much and you risk bleeding, seizures, or heart problems. These are NTI drugs-narrow therapeutic index medications-where the line between safe and dangerous is razor-thin. Yet across the United States, the rules about whether a pharmacist can swap your brand-name version for a generic one differ wildly from state to state. Some states ban substitutions outright. Others leave it up to the pharmacist’s judgment. And a few don’t even recognize NTI drugs as a special category at all.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI drugs aren’t defined by the FDA with a formal list. Instead, they’re identified by experts based on clinical evidence. A drug is considered narrow therapeutic index if small changes in blood concentration-sometimes as little as 5% to 10%-can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects. Common examples include anticoagulants like warfarin, thyroid meds like Synthroid, epilepsy drugs like carbamazepine, and mood stabilizers like lithium. These aren’t just any generics. They’re drugs where consistency matters more than cost savings.

The FDA uses an ‘A’ or ‘B’ rating system in its Orange Book to mark therapeutic equivalence. An ‘A’ rating means the generic is considered interchangeable with the brand. But here’s the catch: the FDA doesn’t label any drug as NTI in that system. That’s left to individual states. So while the federal government says bioequivalence standards are enough for all drugs, pharmacists in many states are told otherwise.

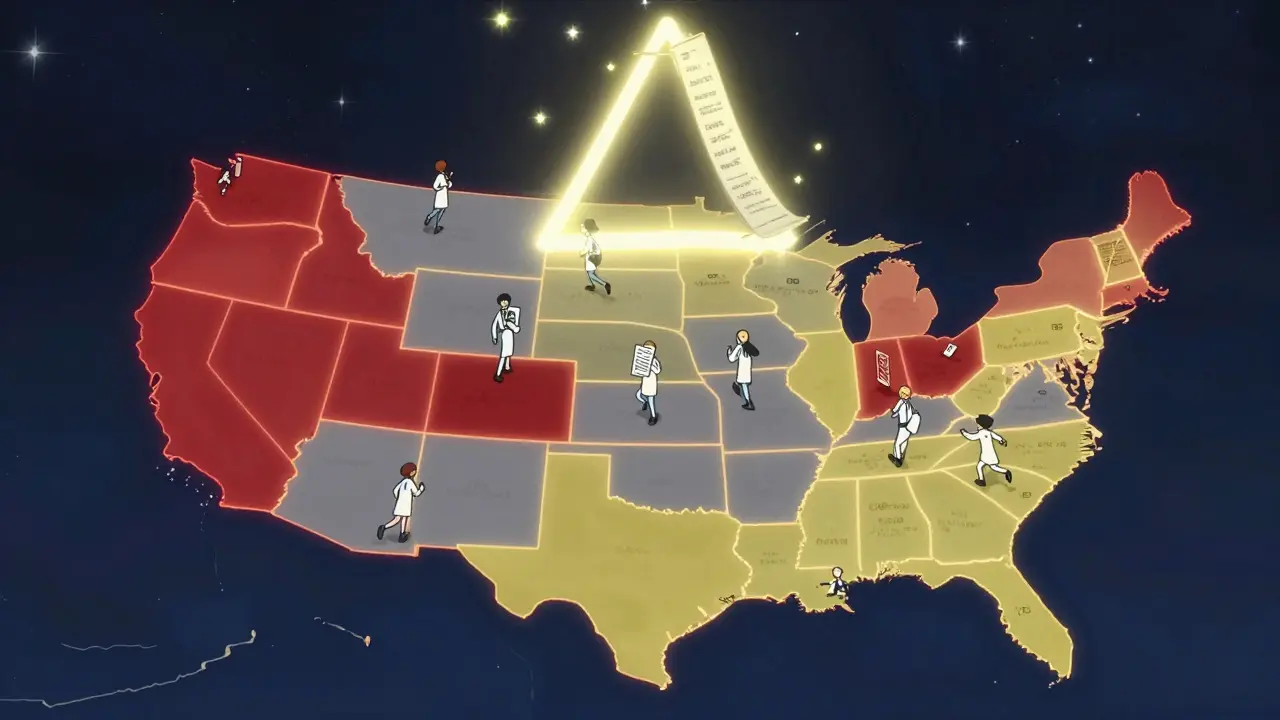

States That Block NTI Substitutions

Kentucky and Pennsylvania have some of the strictest rules. Both maintain official lists of NTI drugs that pharmacists cannot substitute without explicit permission from the prescriber. In Kentucky, that includes digitalis glycosides, antiepileptics, and warfarin sodium tablets. Pennsylvania’s list is similar. If you’re prescribed Synthroid in either state, the pharmacist must give you the brand unless the doctor writes ‘dispense as written’ on the prescription.

South Carolina takes a broader approach. Their regulations don’t just cover NTI drugs-they include ‘critical drugs’ like insulin, anticoagulants, anti-asthmatics (especially time-release versions), and cardiac glycosides. Even if a drug isn’t officially labeled NTI, if it falls into one of these categories, substitution is discouraged. The state doesn’t make it illegal, but pharmacists are strongly advised not to switch.

Tennessee has a unique exception: pharmacists can substitute generic versions of most A-rated drugs, but they are forbidden from swapping antiepileptic drugs for patients with epilepsy or seizure disorders. This isn’t about the drug class alone-it’s about the patient’s condition. A generic switch might be fine for someone using phenytoin for migraines, but not for someone with uncontrolled seizures.

States That Require Notice, Not Block

California doesn’t ban substitutions, but it forces transparency. Under Business and Professions Code Section 4070.5, pharmacists must notify the prescriber whenever they substitute a drug classified as a ‘critical dose drug.’ The state defines this as any medication where a 10% or less change in blood concentration could be life-threatening. That includes many NTI drugs. The prescriber then decides whether to approve the switch or insist on the original brand.

Texas takes a similar but narrower path. Its Health and Safety Code prohibits substitution of anticonvulsants for patients diagnosed with epilepsy unless the prescriber gives written authorization. This law targets a specific population, not a broad drug category. It’s a targeted safety net for those most at risk.

Where the Rules Are Unclear-or Nonexistent

Some states, like Iowa, rely entirely on the FDA’s Orange Book. They don’t maintain their own NTI list. Pharmacists are told to use the ‘A’ rating as their guide and assume all A-rated generics are interchangeable. This creates a big problem: if a drug is flagged as NTI by experts but isn’t labeled as such by the FDA, the pharmacist has no legal reason to hesitate.

In states without any NTI-specific laws, pharmacists are left to make decisions based on personal judgment or institutional policy. That means two patients with the same prescription could get different outcomes depending on where they live. One might get the brand. Another might get a generic-and not even know it.

Why This Patchwork Exists

The FDA’s stance has been consistent since 1997: the current bioequivalence standards-allowing up to a 20% difference in absorption between brand and generic-are sufficient for all drugs, including NTIs. But doctors and pharmacists on the ground see things differently. A 2023 study from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy found that 32.4% of patients stabilized on brand-name levothyroxine saw changes in their thyroid hormone levels after switching to generics. That’s not just a number-it’s a patient who suddenly feels exhausted, gains weight, or develops heart palpitations.

States with strict rules saw an 18.7% drop in warfarin-related adverse events, according to a 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. That’s a small absolute reduction-just 0.3% overall-but for the people affected, it’s life or death. The risk isn’t theoretical. It’s real, documented, and preventable.

What Pharmacists Are Dealing With

Imagine working at a pharmacy chain that spans three states. In one, you can’t substitute warfarin. In another, you can-but you have to call the doctor. In the third, you just follow the Orange Book. Now imagine doing this for hundreds of prescriptions a day, under time pressure, with no centralized database to check.

A 2023 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68.3% of pharmacists who work across state lines have been confused about substitution rules. More than 40% admitted they accidentally broke the law in the past year. That’s not incompetence-it’s a system that’s impossible to navigate.

Some pharmacists have started carrying laminated cheat sheets. Others rely on apps that update state rules, but those aren’t always reliable. In one case, a pharmacist in Tennessee switched an antiepileptic drug for a patient in Chattanooga-only to find out regional practices there were stricter than the state law suggested. The patient had a seizure. The pharmacist was sued.

The Push for Standardization

In January 2024, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy released the Model State NTI Substitution Act. It proposes a single, evidence-based list of NTI drugs that all states could adopt. Twelve states have already introduced legislation based on it. This is the first real attempt to bring order to chaos.

At the same time, the FDA announced in September 2024 that it’s reconsidering its long-standing position. Pressure from the Senate Committee on Aging, backed by a Government Accountability Office report showing nearly 3,000 adverse events linked to NTI substitutions between 2019 and 2023, forced a reevaluation. The Department of Labor also weighed in in early 2025, clarifying that NTI drug rules can affect medical leave under FMLA-because if a patient can’t safely switch meds, their ability to work or care for themselves may be compromised.

Industry analysts predict that by 2027, 38 states will have adopted standardized NTI substitution protocols. That could cut prescription errors by over 20%. But it also means fewer generic substitutions for NTI drugs-potentially reducing their use by 8.3 percentage points compared to other medications. Cost savings will shrink. Patient safety may rise.

What This Means for You

If you take an NTI drug, don’t assume your generic is the same as your brand. Always check the label. Ask your pharmacist: ‘Is this the same as what I’ve been taking?’ If you notice new symptoms after a switch-fatigue, dizziness, irregular heartbeat-contact your doctor immediately. Don’t wait.

Prescribers should write ‘dispense as written’ on prescriptions for NTI drugs unless they’re confident the generic is safe for the patient. Even then, it’s better to be cautious.

And if you move to a new state? Bring your medication list. Ask about substitution rules. Don’t rely on the pharmacy to know them all. They might not.

This isn’t about generics being bad. It’s about recognizing that some drugs aren’t like others. When your life depends on precision, consistency shouldn’t be left to chance-or to a patchwork of state laws.

Are all generic drugs unsafe for NTI medications?

No. Many patients take generic versions of NTI drugs safely. But the risk is higher because even small differences in absorption can affect blood levels. That’s why some states restrict substitutions-not because generics are always dangerous, but because the margin for error is so small. Always talk to your doctor before switching.

Can my pharmacist substitute my NTI drug without telling me?

In some states, yes. In others, they’re required to notify you or the prescriber. In states like California, they must inform the doctor. In Kentucky or Pennsylvania, they can’t substitute at all unless the prescription says so. Always check your prescription label and ask if a change was made.

How do I know if my medication is an NTI drug?

Common NTI drugs include warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, lithium, carbamazepine, digoxin, and cyclosporine. Your doctor or pharmacist can confirm if yours is on the list. You can also look up the drug in the FDA’s Orange Book-but remember, the FDA doesn’t label NTI drugs, so absence from that list doesn’t mean it’s safe to substitute.

Why doesn’t the FDA just create an official NTI list?

The FDA has maintained since 1997 that the current bioequivalence standards (allowing up to 20% variation) are sufficient for all drugs, including NTIs. They argue that clinical monitoring and dose adjustments can manage any variability. Critics say that’s not enough for drugs where even 5% variation can cause harm. The FDA is now reviewing its stance after public pressure and data showing thousands of adverse events linked to substitutions.

What should I do if I think a substitution caused a problem?

Contact your doctor right away. Document the change-note the date, the new pharmacy, and any new symptoms. Request your prescription records. If you’re in a state with strict NTI laws, you may have grounds to file a complaint with your state board of pharmacy. Many states have hotlines for reporting medication errors.

10 Comments

RAJAT KD

8 January, 2026Pharmacists shouldn't be expected to navigate 50 different state laws while juggling 200 prescriptions a day. This isn't a compliance issue-it's a systemic failure.

Meghan Hammack

9 January, 2026If you're on warfarin or levothyroxine, never assume your generic is the same. Always ask. Always check. Your life isn't a cost-cutting experiment.

Angela Stanton

11 January, 2026Let’s be real-FDA’s ‘A’ rating is a joke 🤡. 20% absorption variance for a drug where 5% can kill you? That’s not science, that’s corporate laziness. 📉💊 #NTIisntanoption

Ian Long

13 January, 2026I’ve worked in three states. One had zero NTI rules, one required doctor calls, one banned everything. I once gave a patient the wrong version because the app I used was outdated. No one got hurt-but I haven’t slept right since. We need one national list. Period.

Heather Wilson

14 January, 2026It’s not the generics’ fault-it’s the patients’ fault for not monitoring their labs. If you’re on levothyroxine and don’t get your TSH checked every 6 weeks, you’re asking for trouble. Why should the system bend to negligence?

Also, why do people think their thyroid is special? Millions take generics fine. The ones who react? Usually noncompliant or paranoid. The data shows 67% of reported ‘adverse events’ are from patients who switched back and forth multiple times. Stop blaming pharmacists.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘dispense as written’ nonsense. That’s just a loophole for doctors who don’t want to think. Let the experts-pharmacists and lab techs-do their jobs.

Jacob Paterson

15 January, 2026Oh wow, a whole article about how some people might get the wrong pill. 🙄 Next you’ll tell me we need special rules for aspirin because someone once took too much and got tinnitus.

Let me guess-the people pushing this are either pharma lobbyists or patients who can’t afford brand-name drugs and are now crying because they got a cheaper version. Newsflash: if your life depends on a 5% absorption difference, maybe you shouldn’t be on a $2 generic in the first place.

Also, why are we letting pharmacists make clinical decisions? They’re not doctors. Shouldn’t the prescriber be the one deciding? Or is this just another way to make doctors do more paperwork?

Alicia Hasö

16 January, 2026This isn’t just about pills-it’s about dignity. When you’ve been stable on Synthroid for 12 years, and suddenly your body feels like it’s falling apart because a pharmacist swapped your pill without telling you… that’s not healthcare. That’s betrayal.

I’ve sat in waiting rooms with people who cried because their energy vanished after a switch. I’ve held hands with grandparents who didn’t understand why their heart was racing. These aren’t abstract statistics. These are mothers, fathers, teachers-people who trusted the system.

States like Kentucky and Pennsylvania aren’t being overly cautious-they’re being human. They’re saying: some things aren’t up for debate. Some lives aren’t negotiable.

And yes, generics are fine for most drugs. But when your brain depends on a stable blood level to keep seizures away, or your heart needs precision to avoid clots… then you don’t want ‘close enough.’ You want the same. Every time.

We don’t need more apps. We don’t need more cheat sheets. We need one federal standard. Not because it’s easy-but because it’s right.

If you think this is about cost, you’ve never had to explain to your child why Mommy can’t go to work because she’s too dizzy to stand. This is about safety. Not savings.

Matthew Maxwell

18 January, 2026It’s pathetic that we’ve reached a point where we need state-by-state laws to prevent pharmacists from making life-or-death decisions. The FDA has clear standards. If you can’t trust bioequivalence, then stop using generics entirely. Don’t force doctors to write ‘dispense as written’ on every script like we’re all children.

Patients who complain about switching are often the same ones who skip doses, forget labs, or blame the drug when they don’t follow instructions. The system isn’t broken-it’s being abused by people who refuse personal responsibility.

And let’s not pretend this is about patient safety. It’s about brand-name manufacturers lobbying to protect profits. If you want to pay $200 for a pill when a $5 generic works just fine, that’s your choice. But don’t make the rest of us pay for your privilege.

Pooja Kumari

19 January, 2026I switched from Synthroid to generic last year and I swear I felt like a different person. I was exhausted all the time, gained 12 pounds, and my anxiety spiked. I didn’t even know I’d been switched until I saw the bottle. I cried for an hour. I felt so violated.

My doctor said it was ‘probably not the drug’-but then I switched back and within two weeks, I was me again. My TSH was perfect. My mood was stable. My energy? Back.

Why didn’t anyone tell me? Why didn’t the pharmacist say anything? I’m not a statistic. I’m not a cost-saving metric. I’m a person who trusted the system to protect me-and it didn’t.

I now carry a laminated card in my wallet that says: ‘I take NTI meds. Do NOT substitute. Call prescriber.’ I’ve had pharmacists thank me for it. Others rolled their eyes.

I don’t care if it’s expensive. I don’t care if it’s inconvenient. I care that I can wake up and feel like I’m alive. That’s not a luxury. That’s basic human dignity.

And if you think this is overblown, then you’ve never been the person who lost three months of their life because a pill was swapped without warning.

Ashley Kronenwetter

20 January, 2026Standardization of NTI substitution protocols is long overdue. The current patchwork system creates unnecessary risk, administrative burden, and patient harm. A uniform, evidence-based national framework is both clinically and logistically necessary.